The easy and difficult aspects of learning Basque

Hello everyone! Today I want to share my native language with you: Basque. It's an isolated language spoken in the north of Spain, in the Basque Country, more specifically in the Autonomous Basque Community, Navarra and the French-Basque territory. There are more than a million speakers (if we include passive speakers), and there are increasingly more due to different activities and events that are done to promote the use of the language, asides from its importance within education and the working world.

It's an isolated language, that means that it doesn't belong to any recognised linguistic family. Therefore, it can be a really interesting language to learn, asides from opening the doors to a totally new culture, like the basque culture.

In this article I would like to explain the difficulties and easy aspects to studying this language, most specifically if your native language is Spanish or any other romance language. I don't know the difficulties speakers of other families like germanic, slavic or Chinese would face.

Easy Aspects

1. There's no complex pronunciation

Unlike germanic languages, greek or Portuguese, Basque is spoken just as it is written. We don't have diphthongs that are pronounced differently to the way they are written or combinations of consonants that form another totally different phoneme.

However, there are exceptions; three in particular. The first is -il. Although many pronounce this just as you would read it, this isn't the correct pronunciation. The syllable -il is pronounced like -iy. Some examples are "Uztaila" (July. /ustaiya/) or "Bilatu" (to search /biyatu/).

The second exception is -in. This syllable is pronounced like -iñ, and it's a syllable that appears a great deal in the Basque dictionary. But this can also change depending on the word, meaning, if the syllable -in appears at the end of the word (like "orain", ahora/now), the phoneme /iñ/ isn't as strong, it could even be a simple /in/. However, in the rest of the words like "baina" (but), "adina" (age) or "egina" (made, particple of the verb 'to do'), the phoneme /iñ/ is significant.

The third exception is the combination "tt", something that only exists in Basque dialects, not in standard Basque. This double "tt" is referred to as "t bustia" (wet t), due to being a mix between the Spanish /ch/ and /t/. It's common if you can't pronounce it initially, many people still cannot, but it's a question of listening to people say it. Sooner or later it'll come to you unconsciously. Some words that may contain it are "Aittitte" (grandad. In standard Basque it is "aitona") or politte (pretty. In standard it changes to "polita").

But it doesn't end here, there are more exceptions. In the Bizkaia Province it may not be noticeable, but in Gipuzkoa people can tell the differences in vocalisations of the syllables "ts", "tz" and "tx" or the "s" and the "z". In Bizkaia it's not that common, but in Gipuzkoa the "z" is pronounced with a sound similar to a snake. It's really difficult to explain in writing, but if you look on the internet you can hit the nail on the head. I've never been able to pronounce this snake-like "z", the "tz" either.

In Bizkaia what we do say differently is the "x" of the other two letters, because we pronounce it like the English /sh/ but in a deeper tone. It's a sound similar to the onomatopoeia of silence ("shhhh"), but a little stronger. In Bizkaia we also have other types of sounds that we include in our language (influence of the Bizcayan dialect), but I'll explain them as we go along.

2. There are a lot of neologisms in Basque

Given that Basque doesn't belong to any existing linguistic family and, as a consequence of its oppression throughout history, it's lost many words that have been substituted for Spanish, French and Latin neologisms, as we can see with "eliza" (iglesia/church. "ecclesia" in Latin), "gorputz" (cuerpo/body. "corpus" in Latin) or "balea" (ballena/whale).

Due to the disappearance of many words, during the 19th Century the politician and writer Sabino Arana invented new words for Basque, with the intention that the Basque dictionary wouldn't be full of neologisms, naming them 'sabinismos'. So, he was able to firmly establish words like "idatzi" (to write), "lehendakari" (president), "argazki" (photo), etc.

But despite all this effort, there are still lots of neologisms. Many belong to the scientific and technological field, but there are many other words far removed from these fields like funtzionatu, airea, interakzio, auto, telefono, ordenagailu, barietate (variety), letra, txokolate, prozesu, familia, etc. However, many synonyms exist for these neologisms and many others, like "mugikorra" to refer to "telephone", "elkarrekintza" in place of "interakzio", etc. Unfortunately, society has preferred to use neologisms given that they're closer to Spanish, so it's easier to remember them.

But, we have words that aren't similar to any other language, and many with very important meanings. For example, the word "harresi", means "wall" and more specifically "the wall of stone", or "ekhilore/eguzkilore", which means "sunflower. the flower of the sun". Not long ago a thread went viral on twitter which mentioned the meanings of Basque words like "bihotz" (Heart. Two voices), "otsaila" (February. Month of the wolves), "amona" (grandma. Good mother), and a very long list of others.

From there you can clearly see the beauty that Basque has, given that many words are well thought out and it gives the sensation that it was created with a lot of love.

But there are also words that are intended to be translated to an equal definition in Spanish, like we can see with "urtebetetze" (cumpleaños/birthday, can only be translated as birthday), "telelaguntza" (teleservice, translates as tele-help) and many others.

Other words with translations (unique that have no similarity with the relevant words in Spanish) are:

- Ur-jauzi. Cascada/Waterfall, water that falls

- Aterpe. Lugar cubierto/covered space, under the door

- Maitemindu. Enamorarse/To fall in love, heartache

- Bihotzerre. Acidez/Acidity, heartburn

- Hegazti. Ave/bird, he who flies

- Eskumutur. Muñeca/Wrist, the edge of the hand

- Ilargi. Luna/Moon, the light of the dead

- Amuarrain. Trucha/Trout, hookfish

- Eguraldi. Tiempo/Weather, the moment of the day

- Itsasargi Faro/Lighthouse, the light of the sea

3. There are no written accents in Basque

This is a big advantage. Unlike the rest of the languages that surround it (Portuguese, Catalan, Spanish, Galician, Occitan, French, Italian... ), Basque has no type of written accent, but it does have accents. The accents can be because of dialect, but normally they are similar. Something that can be a bit "difficult" is that some words have two accents, as we can see in irakasle. The first accent would be on the first "a", which would mean it is stressed on the third-to-last syllable. The second accent would be on the last letter, meaning, on the "e", but this accent is softer.

However, each dialect has their way of pronouncing words. Although the word "irakasle" (profesor/a - teacher) doesn't exist in my dialect. In my dialect "maisu" is said for the male gender and "andereño" for the feminine), in standard Basque, I would pronounce it: "irakásle". I wouldn't put any accent on the two vowels previously mentioned but only the one that's in the middle.

This situation happens often, so don't stress if you don't grasp the accent immediately, it could be that you've done it just like a some of the dialects. Normally the second syllable is accented, and when the word has two or three syllables, it's the first that's accented.

However, some dialects go a bit further from this simple rule. Here, in Bizkaia, when we want to refer to "el niño/the little boy" we say "umié", putting stress on the last vowel, but when we want to say "los niños/the boys" we say "umíek". Likewise, when "el niño" is the subject of a transitive sentence, the word changes to "umiék" (the "l" defines the ergative), and in the case of "los niños", the stress doesn't change, meaning, it stays "umíek". It can be really complext, but this only happens with dialects, at least in Biscayan.

4. There aren't genders either

In Basque gender cases doesn't exist, whether in nouns or adjectives. If we want to translate the sentence "el chico es guapo (the boy is handsome)" and "la chica es guapa (the girl is attractive), we translate them to "mutila polita da" and "neska polita da". Here we make the difference between the girl and the boy because 'niño' is "mutila" and chica, "neska"; however, we don't mark the gender in the adjective. What happens with professions? They don't have gender, for example, to say 'enfermero/a' (nurse) we say "erizaina" without differentiating gender, or "sukaldaria" to say cocinero/a (chef).

There isn't any gender in the 3rd person personal pronoun, singular or plural. To refer to "him" and to "her", we say "bera". There's no gender. The same occurs with the 3rd person plural ("haiek") and demonstrative determiners ("hau", "hori" and "hura" to say "this", "that" and "that one"), among others.

However, you can identify the gender of animals in sentences, given that to say, for example, "gato" (male cat) we say "katua", but to say "gata" (female cat) we say "katu emea" ("eme" meaning female).

DIFFICULTIES

1. It has no genetic relation to any other language in the world

Basque doesn't belong to any linguistic family in the world, therefore, it is an isolated language. Many researchers have proposed theories about the genetic relation of Basque with Caucasian or Berber languages but none to any avail. We are talking about a language that has been in the Basque peninsula even before the Indo-European languages arrived.

Because of this, many of the words have no relation whatsoever with the other languages, and if you don't believe, I'll cite various examples, as I did in a university project:

Western European Languages: piedra (Spanish), pedra (Portuguese), piatra (Italian), Stein (German), stone (English), harri (Basque).

Eastern-European Languages: estrella (star). Stea (Romanian), zirka (Ukrainian), zvezda (Russian), asteri (Greek), zvezka (Serbian), gwiazda (Polish), hvězdička (Czech), stejrners (Norwegian), izar (Basque). We can see that there are similarities amongst some, like Romanian, Greek and Spanish; Norwegian and English (star); Russian, Serbian, Czech and Polish. But, what about Basque?

It's true that Basque is full of words stemming from Greek, Latin, Celtic languages, German and Arabic, but it contains words that have no relation with the rest of the world at all. It's for this reason that the language is difficult to learn.

2. According to the area, vocabulary changes

This is something we've already seen. Due to the expanse of Basque (not huge but varied) and all the isolated territories within it (because of the mountains), each village has been shaping their dictionaries individually. In total there are seven Basque dialects, but within each one there are different ways of speaking, just like that of Andalusian territories or Castillian-Moncha territories.

Whilst in standard Basque, "pulpo" (octopus) is translated as "olagarroa", in places like Bermeo they say "amorrotza" and in Getaria, for example, "alarrua". In the same way, whilst "berehala" (shortly) is said in standard Basque, in some places they say "belaxe", "laixterka", "kuxian", "agudo", etc.

But to make these comparisons you don't have to go very far. In my city, Gernika, we say "arin" to say "quickly", but in Busturia, a municipal 8km away, they say "agudo" (similar to in "berehala") and in Mendata, 7km away, they say "abiedan".

Generally, words change according to the area, but not just nouns and adjectives, but also conjunctions, flexible verbs, the same verbs, etc.

But this doesn't add much difficulty to talking to a Basque speaker, given that the majority understand Batua Basque, and there's no issue and you speak to them in standard Basque. It could be that they change from dialect to standard, but in the case that they don't - ask them. You won't encounter any issues.

3. The word order and the ergative case

The word order is one of the biggest difficulties for a Spanish speaker. The word order in Basque is SOV, meaning, Subject-Object-Verb, unlike in Spanish and English, whose order is SVO (Subject-Verb-Object).

For example, the sentence "el perro quiere comer" (the dog wants to eat), we say "txakurrak jan nahi du" (the dog to eat wants). Here we can see another really complex characteristic of learning Basque: the ergative. It's a case that differentiates a transitive sentence from an intransitive through just one letter: the "k". In the transitive sentence there's a direct object, and the intransitive sentence, on the other hand, doesn't have one.

A transitive sentence is clearly demonstrable in this sentence: "the house has cracks". Here you can identify the direct object ("the cracks"), and because of this it's a transitive sentence. In this case, the translation to Basque would be "etxeak arrailak ditu".

The morphological analysis of the noun phrase in Basque would be like this:

Etxe (house) + a (gender article) + k (ergative case).

In the case of a plural, "etxeak" would become "etxeek" (etxe + ak (plural definite article) + k). In this situation, the letter "a" of the definite article turns into "e", given that "etxeak" can mean "the houses" in the intransitive case and also "the house" in the transitive case. And that isn't what we're looking for.

On the other hand, the intransitive sentence would be "etxea eraitsi egin da" (the house has been demolished), because there is no direct object. To be clear, you can check any doubts by looking at the preterite perfect compound of French (passé composé), given that they differentiate the transitive verb (by using the verb "avoir", which means "to have". For example: il a jeté l'éponge. "he has thrown away the sponge") from the intransitive verb (using the verb "être", which means "to be". For example: je suis parti. "I have gone").

Continuing with the theme of word order, this can complicate things depending on the length of the sentence. Given that the verb has to be positioned at the end of the sentence, the longer the phrase, the more difficult it will be to form a sentence.

As an example we can take the sentence "la chica me preguntó si quería comer con ella" (the girl asked me if I wanted to eat with her). If we translate this into Basque, the sentence would be "neskak berarekin jatea nahi nuen galdetu zidan". If we analyse this word for word, the literal translation is: "neskak (the girl, ergative case) berarekin (with her) jatea (to eat, although not in the infinitive form) nahi (to want) nuen (if + I, past tense) galdetu (to ask) zidan (her to me, past tense)".

The topic of verbs will be explained in the next bullet point.

However, to be able to understand better and in more detail the Basque word order we need a longer sentence, which could be: "la chica de la peluquería me preguntó si podría recoger a su hijo menor después de que saliera de clase a las cuatro de la tarde" (the girl at the hair dressers asked me if I could pick up her youngest son after he leaves class at four in the afternoon). Forming this sentence in Spanish/English is easy, but in Basque?

Let's see, the translation would be more or less: "ileapaindegiko neskak galdetu zidan bere seme txikia jaso ahalko nuen bera klasetik irten eta gero, arratsaldeko lauetan". It's certainly not an easy sentence.

Because of the length, it's impossible to put the initial verb (in this case "galdetu") at the end, so we put it after the subject. The literal translation would be this:

- Ileapaindegiko (at the hair dressers).

- Neskak (the girl, in the ergative case).

- Galdetu (ask).

- Zidan (her to me, past tense).

- Bere (her).

- Seme (son).

- Txikia (little, youngest).

- Jaso (pick up).

- Ahalko (be able to, in conditional. You can also say "ahal izango").

- Nuen (I to him + the conjunction "if").

- Bera (him).

- Klasetik (from class).

- Irten (leave).

- Eta gero (after).

- Arratsaldeko (in the afternoon).

- Lauetan (at four).

This sentence ends in the same way as it does in English/Spanish, with "at four", but this doesn't happen a lot of the time.

I don't know if you'll have been spooked by this, given that it's quite difficult to understand, but over the course of time you begin to understand easily that you can produce sentences like this unconsciously.

4. Aspects of the verb

In Basque there are two verbal forms: verbs that are composed of two or more words (periphrastic verbs), like for example "jan egin dut" (I've eaten); and verbs formed with just one word (concise verbs), like "dakarzu" (you bring).

There aren't so many concise verbs, this can only be seen with the verbs "ekarri" (bring), "izan" (be), "eduki" (have), "eraman" (carry), "ibili" (walk), "jakin" (know), etc. But don't think that just because it's one word that makes it easy, because in Basque it's the opposite.

To demonstrate this, let's look at the conjugation of "eraman":

- I: daramat (I bring).

- You: daramazu (you bring).

Or let's look also at the conjugation of ""ibili"

- I: nabil (I walk)

- You: zabiltza (you walk).

On the other hand, the conjugation of periphrastic verbs is easier, because the same thing applies to them all:

For example, in the conjugation of "jan" (eat):

- I: jaten dut (I eat).

- You: jaten duzu (You eat).

Or the conjugation of "abestu" (sing):

- I: abesten dut (I sing).

- You: abesten duzu (You sing).

The Nor-Nork verbal system is used all the time, although if you add direct and indirect objects into the sentence, the verbal system changes. But don't worry, I'll expand on this below.

To refer to the infinitive, similarly to in Spanish (whose infinitive verb endings are categorised into -ar, -er and -ir) there are various types: the verbs that end in -tu, -n and -i, like "ospatu" (celebrate), "egon" (be) and "ebaki" (cut). There are also verbs that are accompanied by other verbs, in this case the verb "egin" (do), as we can see in "igeri egin" (swim) or "negar egin" (cry).

As with many other languages, there are verb tenses in Basque, but less than in Spanish. In Basque we have the present, future and past indicative, the subjunctive, the conditional, the potential (in Basque it's called "ahalera") and the imperative.

What's this potential tense? The translation into English would be: I can, I could, I used to be able to, I would be able to", in other words, the verb "can"/"to be able to". But the potential isn't as easy as it seems, given that for many it can seem like a true hell on Earth. The same happens with the conditional case, which is split into three forms: the conditional (if), the consequence of the past and the consequence of the present. What does this mean? Let's have a look at this sentence:

"If I did that, I would have lost my hair"

"If" would be the conditional, and "I would have lost", on the other hand, the past consequence.

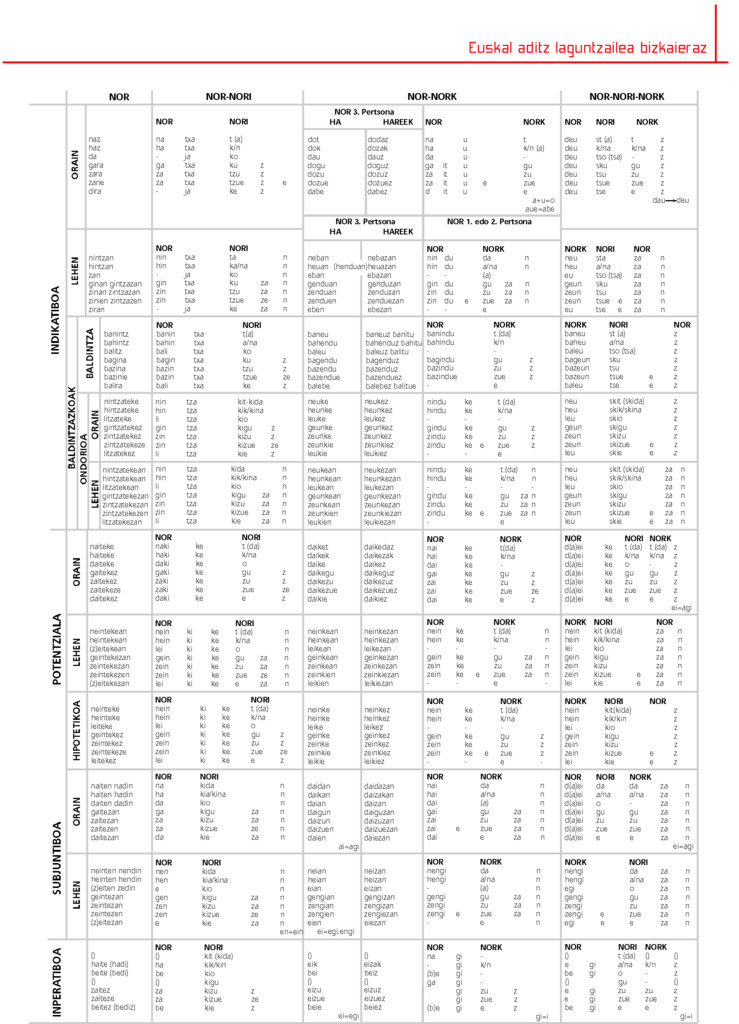

All of this forms part of a complex verbal conjugation, given that according to the person who does the action and the person receiving the same action, the verb changes completely. As a clear example, I've put here the verb table of the Biscayan dialect, but if you're interested in knowing the verb table of standard Basque, there are lots of webpages where you can easily find it.

5. Verbal Systems

This topic is also relevant to the image above. Basque has four systems from which the auxiliary of the verbs combined by more than one word are conjugated. Those four systems are the following (although you can see them clearly on the image above):

Nor.

Nor-Nork.

Nor-Nori.

Nor-Nori-Nork.

We'll start one by one. The "Nor" system is the simplest, and it means "who". It's used when there isn't a direct object in the sentence, meaning, in an intransitive sentence. A really good example would be "This morning I drove". The sentence in Basque would be "Gaur goizean gidatu egin dut", and "dut" would be the auxiliary from the Nor system.

The verb tenses in this system are like the rest: the present and past indicative, the three forms of the conditional (conditional, present consequence and past consequence), other three forms of the potential (present, past and hypothetical), the past and the present subjunctive and the imperative. This system doesn't follow different rule of conjugation from the other three, but the system is easier to learn/ What's more, it's the most used.

But what happens if future and past perfect conjugations don't exist in Basque? It'll depend on the inflexion of the main word of the verb, for example:

- I am falling down ni erortzen nago.

- I fall down: ni erortzen naiz.

- I have fallen down: ni erori naiz.

- I will fall down: ni eroriko naiz.

- I would fall/I was falling down: ni erortzen nintzen.

- I would fall down: ni eroriko nintzen.

- I fell down: ni erori nintzen.

As you can see, the principal verb (jan) changes depending on the tense. So, when the auxiliary is the same in the different verb tenses (like "naiz", in this example), the inflection in the main verb to identify the tense in which the action takes place.

This system is used with verbs of movement, like these: ibili (walk), joan (go), etorri (come), igo (rise), etc. They also form part of the verbs "egon" (be), "gaixotu" (to be ill), "haserretu" (to be angry), etc.

The second system is Nor-Nori, a little more complicated. Here, the Nor refers to ""who or "what" as the protagonist or doer of the action, and the "Nori" refers to "to whom" as the receptor/receiver, but it isn't that easy, given that the following system "Nor-Nork" is similar. Having said that, there is a notable difference in the two systems, because in Nor-Nori, sentences are intransitive.

Examples of Nor-Nori are:

- I like planes "Planes is Nor and Nori would be "to me".

- You have dirtied your shirt. "Shirt" is Nor and Nori, on the other hand, ""to you".

So, "I like that plan" would translate to Basque as "Hegazkin hori gustatzen zait", with the auxiliary being "zait". But if we say "I like those planes", the auxiliary would change to "zaizkit", which would be the plural.

All the sentences that can be made with this system are very similar to those two examples above. But also there are other more difficult models, like "our daughter has got married", "it's in my interest to lose weight", "the electrician has come to my house", etc.

The Nor-Nork system appears in transitive sentences (those that don't have a direct object), like "I've broken the screen" or "I've deceived you".

The sentence "I've broken the screen" would be translated like this: "nik pantaila apurtu dut". The "I", given that the sentence is transitive, needs to carry the ergative mark, meaning, the -k. This way, this "ni" (I) turns into "nik". On the other hand, dut would be the auxiliary of the verb "apurtu", conjugated depending on the Nor-Nork system. If it were another verb tense, like the conditional consequence ("I would break"), it would be "nik pantaila apurtuko nuke".

But this isn't it, it gets more complicated. When there is more than one person present in the sentence, the conjugation table changes. For example, the sentence "you have hurt me" would be translated as "Zuk mindu nauzu". "Zuk" would be "you" with the ergative case, and "nauzu" the auxiliary. On the other hand, if we say "I have hurt you", it would be "nik mindu zaitut", and the auxiliary form would completely change, without a similar root.

Finally, there is the Nor-Nori-Nork system. Despite having the longest name, it isn't the most complicated. In these sentences there are three elements. Normally they are composed of two people and an object, but there are many variations, like one person and two objects, three people or three objects. Nork is the subject that completes the action, Nor is the object and Nori is the other subject, but that which receives or perceives the action. This explanation can be summed up clearly in this sentence: "My mother has lent me money". "My mother" would be Nork, "me" would be Nori and "money" would be "Nor".

As we've seen in Nor-Nork, the example we've used has been "you have hurt me", but what happens if we say "you have done me harm"? The verb system changes.

Furthermore, this sentence in Basque would be "zuk min egin didazu". "Zuk" is Nork, "min" Nor and "me" (omitted) Nori. The auxiliary is "didazu", and the auxiliaries in this system don't change too much, although they are longer, like for example "zenizkidaten" (you to me several things, in the past) or "dizkiguzue" (you to us various things, in the present).

And that's everything! Despite there being lots of characteristics in Basque that seem complex, like the relative pronouns and subordinate sentences or the position of prepositions, or those that seem easy like the smaller vocabulary and synonyms or the lack of a personal pronoun of politeness (in use, although there is one that exists but it isn't common), I think everything previously mentioned is enough to help you and warn you about Basque grammar with its pros and cons.

Love to all and until next time!

Photo gallery

Content available in other languages

- Español: Facilidades y dificultades al aprender euskera

- Italiano: Pro e contro dell'euskera

Want to have your own Erasmus blog?

If you are experiencing living abroad, you're an avid traveller or want to promote the city where you live... create your own blog and share your adventures!

I want to create my Erasmus blog! →

Comments (0 comments)