Using Animals for Food & Fashion: A Look at Species Bias

Why do we empathise with dogs but not pigs? Will it ever be acceptable to wear cats as fur? Is it okay to eat dolphins? By what margin are humans the most intelligent species? These are questions which force us to reflect on our species biases in food and fashion…

Animals as Food

From an evolutionary standpoint we are, for the most part, all supposed to enjoy the taste of animal flesh.

But as we enter a new age of technology and (hopefully) new moral standards, with factory farming causing not only environmental damage, but also inflicting needless suffering to other intelligent species, and accounting for 90% of all produced meat - an ethical dilemma arises: does the enjoyment gained from eating another animal justify humans eating as much non-human animal flesh as we see fit?

In this article we shall attempt to discover what obligations, if any, we have as the most intelligent (and dangerous) species of animal in our known world; that is, by gauging whether or not we have a duty to respect the lives of other sentient beings. Do animals have rights? That is an issue that won’t be discussed at great length throughout this article. There are also many other instances which raise huge ethical questions such as this one, for example the idea of using animals in testing and research, which for the nature of this discourse I have largely omitted so as to focus on the main issues which are prevalent in our personal consumer choices. However what this article will aim to do is highlight our relations with other species, uncovering in the process our own species bias for other humans and indeed, those we choose to deem as pets over those we choose to deem as food. The discourse may force us to ask ourselves some difficult questions at times, and may even force us to act against our own intuitions, but this may be necessary in order to reveal the extent of the species biases we carry.

So ought we, as a highly evolved species of animals ourselves, to give more consideration to the lives, preservation, and yes, even feelings of our other animal counterparts? The word ‘feelings’ may come as a surprise when discussing the wellbeing of animals. However, there is no longer any debate as to whether or not animals can ‘feel’ emotions; the fact that animals have feelings is now conclusive. Research has indicated farmyard animals, including cows and pigs, are capable of processing complex emotions such as fear and loneliness. In fact, cows show demonstrable signs of loneliness when separated from their mates or family similar to the type of separation anxiety displayed by dogs when separated from their owners.

Before we delve any further into species comparisons, let us focus on another pressing issue for a moment: Global Warming. From an environmental perspective, eating cows is an issue fraught with ethical issues. For example, it takes anywhere between 442 - 8000 gallons of water just to produce one single pound of beefsteak (the average is actually 2, 500 gallons). To put that figure into perspective, in comparison, it takes 1. 1 gallons of water to grow a single almond, 3. 3 gallons to grow a tomato and 4. 9 gallons to grow a single walnut. Evidently, we need to make conscious environmental choices regarding all types of food we eat and not just about animal products. But it would be ignorant of us to deny how much more damage is being caused to the environment through animal products than by plant-based options.

There are 1. 5 billion cows on the planet, which are all reared for the purpose of meat and dairy as well as leather products. Recent documentaries such as ‘Cowspiracy’ have brought into the mainstream the issues regarding the livestock industry, and anyone who has seen such documentaries may already be aware that animal agriculture accounts for 18% of all greenhouse gas emissions – which is more than all modes of transportation put together (which accounts for 13%). In a society which is now attempting to undo the wrongs of greenhouse emissions through the means of ‘clean energy’, shouldn’t the primary issue be first that of tackling the mass production (and consumption) of more than 1. 5billion creatures that produce over 150 billion gallons of methane gasses per day? This isn’t to say that the only way of protecting the environment is by abandoning eating animal products, but it is evident that this should be our chief concern.

We will now address the issue of animal preference and species bias by comparing the morals of eating one beloved animal (dogs) over another less beloved: pigs

Animal bias?

Can eating bacon be compared to eating dogs? The mere thought of dog eating is enough to drive some Western minds so far to repulsion that they may scoff at the argument altogether, choosing to assume that comparing the two is an argument that simply can’t be made. There are however, some striking similarities between not only pigs and dogs, but also between pigs and humans. Pig flesh is one of the most sought after and consumed delicacies across Europe, particularly in areas such as Spain where products such as ‘jamon’, dominate the meat market. In regards to the act of eating dogs however, there are certain areas in China such as Yulin where the annual dog eating festival takes place; a practice which would be condemned not only in Spain, but also across the wider world. This suggests that the taboo of dog eating is a cultural phenomenon, and is clearly not so repulsive in some cultures as oppose to others.

The history of human’s relationships with dogs is long and complex. Dogs have been seen as companions to us Homo sapiens for thousands of years and there are even some hypotheses, which suggest that their resultant evolution (and subsequent survival) from their wolf ancestors came about through their befriending of humans. Naturally, it is due to this length of exposure to dogs as pets and companions that leads many of us to a repulsion of eating them. However, our early primate ancestors were cunning creatures themselves and at times wouldn’t have hesitated to eat their ‘pet’ dog when food supplies were scarce. One may argue however that our affections to dogs run much deeper than this, that our attachment to them is due to their ‘intelligence’ or the ‘human-like qualities’ they possess. Judging by these parameters, to eat one animal over the other purely because one had qualities reminding us of our own species would not only make us incredibly narcissistic, it would also make us speciesist.

Granted, it intuitively may on some level be more wrong to eat your neighbour’s dog rather than eat the bacon you bought from the store. But this is not simply due to the fact it could severely upset your neighbour - not to mention irreparably damage your relationship with one another - but also due to the issue we’ve just raised; that historically, we have become attached to dogs rather than pigs. Furthermore, our neigbour’s dogs live in far a higher luxury and comfort to that than any factory farmed produced pig would every live to see. So with this idea of dog companionship put to the side for the moment, let us now finally contrast the act itself of eating dogs with eating pigs.

Is eating a pig equivalent to eating a dog?

It now seems reasonable that we should return to the subject of intelligence, namely how a dog’s intelligence is one of the reasons we may provide for not eating them. The notion of dogs as ‘family members’ often derives from the fact that they are incredibly intelligent as well as intuitive creatures that seem to comfort us and appease us when we need it most. If we are measuring the act of not eating dogs down to intelligence however, this would also rule out the consumption of pigs, as pigs have been found to display even higher levels of intelligence than dogs. Similarly to dolphins and elephants, pigs are able to identify themselves in a mirror and, somewhat incredibly, some have even been taught how to play basic video games - a skill which has also been taught to some highly intelligent species of primates. Pigs are even capable of dreaming - which isn’t exclusively a human phenomenon - and also respond to their own names when called in the same manner as dogs do.

It may be argued, a pet dog reacts to it's owner in certain ways in which it doesn’t react to other humans, or in ways other animals don’t react to humans either. But this isn’t to say a pig wouldn’t be capable of responding in a similar manner if exposed to humans for as long a period of time and in the same manner. In fact, most pigs are known to be highly loyal and affectionate creatures towards humans and, similarly to dogs, enjoy being stroked and groomed. Dogs have essentially became as “good” with humans as they are simply because it was in their own interests as a species to survive by doing so, even if it meant that the occasional one had to be sacrificed for supper when human food supplies ran short. It should be said here that it is not in a pig’s survivalist interests however simply to keep their species alive through a life of degradation purely for human interests. The shocking truth is that these highly intelligent creatures are often driven to insanity through living in cramped conditions such as tiny, barbed metal cages, so small that they can barely move - far below any standard of comfort we’d assign to any human or dog – all for the means of human consumption.

In regards to having ‘human-like qualities’ - in a similar manner to how we make room for not eating dogs – this can now also be argued in a similar favour for not eating pigs. In fact, it is believed in the traditions of Islam and Judaism that eating pig flesh was not outlawed due to the much misled assumption of being a ‘filthy animal’, but rather because the slaughtering of pigs during the preliminary eras of these new religions and cultures culminated via measures which involved excruciating pain to the pigs, resulting in a loud, now somewhat infamous ‘squealing’ sound - a sound which reminded pious folk so much of the sound of a human crying out in agony, that they decided there-and-then against eating the animal altogether.

Arguably, if it is intelligence that we are marking our eating habits by (and this often appears to be the case) should it be that we only allow ourselves to eat animals that are far less intelligent than us? If so, why does intelligence even matter? There are many animals of higher intelligence than certain humans - without any sinister joke or malice intended here, there are indeed certain people, be they underdeveloped or unfortunate, who are far less intelligent than say, fully developed pigs or cows. To continue with pigs as our example, no other animal is believed to have a more similar kind of flesh to humans than pigs, as well as sharing an incredible amount of other various genetic similarities. So much so, pigs are now used as models for human dermatological diseases. This seems a rather bold admission by health professionals as to the striking genetic similarities between humans and pigs. So in light of this evidence, and perhaps surprisingly, we are now faced with a case which no longer weighs in favour of eating pigs over dogs - on the contrary, pigs clearly have more in common with humans beings than dogs do. This begs the question: just how far removed from our own species does another nonhuman animal have to be before we begin to consider if it is morally acceptable to eat it? Is it simply the taste of its flesh which determines whether we should eat it or not?

Is there a difference between Cannibalism and Eating animals?

It’s an interesting point to discuss that many people exposed to burning human bodies such as professionals involved in cremation and firefighting, often report a strong scent of pork emanating from burning human corpses. Whilst the thought of cannibalism may unnerve most of us, taste-wise, to give an extreme example, this recognition of pork having a similar scent to burning human flesh - matched with the knowledge of pigs having near-identical skin to us - suggests there may be very little difference between the taste of a pig and that of a human. And if we bring the argument of intelligence back into play, it follows that rationally, if it is acceptable to eat a fully grown intelligent pig who is capable of processing emotions as well as suffering and feeling pain, it is therefore also rationally acceptable to eat a particular human, who to a much lesser degree can’t process or possess these attributes. Our preference for choosing to eat one particular animal which isn’t one of our own species, and one which is clearly more intelligent than certain people of our own species - particularly in cases where both may in practice taste exactly the same (as in the case with human flesh and pig flesh) - is another clear case of speciesism. This is by no means an argument that we should result to cannibalism; contrastingly, it is the precise opposite. It is an argument intended to make us realise our own species bias and hold the same contempt towards eating other species as we do to our own.

But our species bias runs much further than that of our own species and pets. There are even particular animals, such as horses, who most people would feel repelled towards eating, due to the notion that they are commonly valued as ‘majestic’ creatures, whereas pigs are wrongly labeled as filthy. One key example of this was the European horsemeat scandal in 2013, where processed meat companies were found to have included horsemeat rather than beef in their products as a means to cut costs. Many people were outraged, even horrified, yet this still wasn’t enough for many to realise their own hypocrisy: that eating a horse is not morally (or apparently taste-wise) any different to eating cow’s beef, in the same way as eating a dog is of no real moral difference to eating a pig.

Admittedly, it does make sense evolutionarily that we are more horrified by the thought of eating our own species than another. Animals who could emphasise and feel connected to members of their own species had a higher chance of survival, hence why human life has flourished, with the population reaching over 7 billion people. But just because we’ve developed thus far as meat-eaters evolutionarily, that is not to say we don’t now have the choice to do act differently.

Where exactly does the distinction lie between eating a human and eating a non-human animal – what exactly makes eating one acceptable and the other taboo? Are we still so brainwashed by religious texts that proclaim humans own the rights to all other species? With science pressing not only the boundaries of belief further but also demonstrating the emotional and intellectual capacity of our fellow creatures, we have every right to question this age-old dogmatic false assumption that humans possess souls, which our animal counterparts supposedly lack. Humans are clearly not as distinct from our non-human animal counterparts as we once thought. Even the heavily lamented chicken - which has often been given the unfair reputation of being a "bird brain", despite there now being resources indicating that chickens are capable of having complex social relationships with one another and can likewise respond and show preference to their own family members, much like ourselves and other species. Scientists have also uncovered that dolphins, which are considered a delicacy in areas of Japan, use complex forms of communication; a striking discovery which has revealed humans are not the only species to have developed their own form of spoken, intelligible language.

- “This (dolphin) language exhibits all the design features present in the human spoken language, this indicates a high level of intelligence and consciousness in dolphins, and their language can be ostensibly considered a highly developed spoken language, akin to the human language. ”

So do we condemn those who eat dolphins but not those who eat chickens? Do humans have a soul but not dolphins? This notion seems absurd. To claim special rights to existence over other creatures, who share many of our own traits, is a falsely given assumption that we have some inherent right as human beings to use other sentient beings who share this planet with us as we see fit. When we use terms such as ‘right to life’ and ‘life is sacred’ we are usually only talking in regards to humans. In light of recent evidence, we now must admit that these statements should similarly apply to other non-human animals.

Jeremy Bentham: “The question is not, can they reason? Nor, can they talk? But, can they suffer? ”

It is fair to assume that most people would agree that suffering is bad. If we agree with this, then it is also fair to assume that any unnecessary suffering should be prevented. Therefore we must conclude that if we can prevent any being capable of feeling pain from suffering, we ought to do so. With the knowledge that us, as a species, are inflicting unnecessary suffering in the world by producing and consuming animal products made via factory farming, should we still continue to buy products from these industries that harass and deprive other species for the sake of mere indulgence to ourselves? How do we go about justifying this?

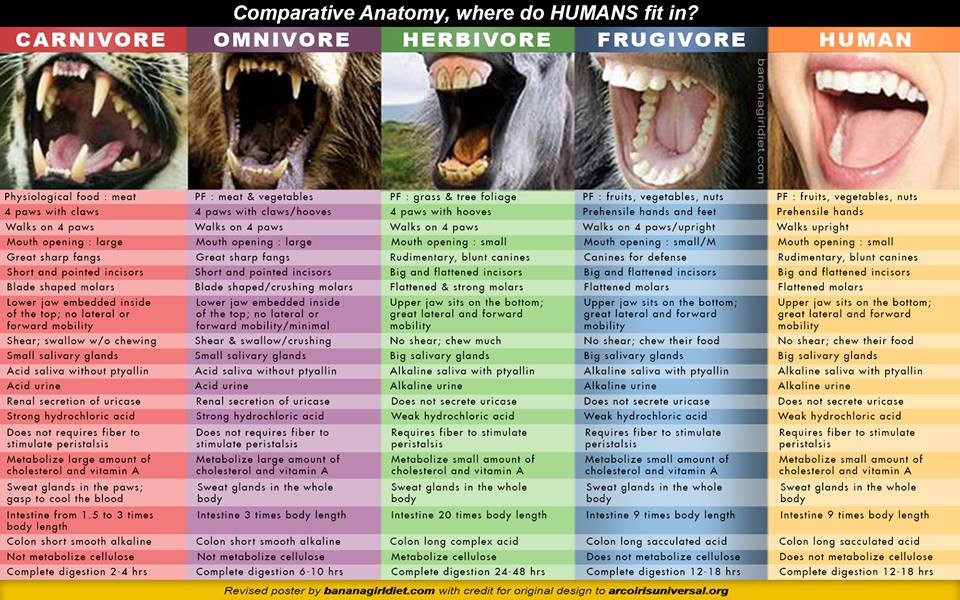

The question now isn’t simply a case of whether or not to eat animals. The question is, under the current circumstances: is it morally right to do so? Can we justify our evolutionary instincts and urges to eat meat in light of the subjugation we know that animals go through in intensive, squalid, factory farm conditions? Just because we have an ‘urge’ to do something, doesn’t then mean we should act upon it. It would clearly not be in human interest if every member of our species acted according to their own ‘evolutionary urges’ on every matter, be it sexual, survival or dietary. Meat is a luxury not a necessity. To refrain from eating it doesn’t hinder any further chance of human survival, on the contrary, it may even be of benefit to exclude it as a source of food intake for this very reason, and it is likewise no longer necessary to consume it in order to increase our chances of survival or for further evolution. The counter argument that we ‘need meat’ or that we grew larger brains after adding meat to our diets during our evolution carries no validity, as the size of the human brain has in fact shrunk 5% in the last 10, 000 years. Contrarily, both dietary and evolutionary wise, one could argue we may even have more in common with frugivores, such as chimpanzees and orangutans - who share more than 98% of our DNA - than we do with omnivoress, such as lions and tigers:

One argument from one who sees nothing wrong in eating animals per se, but sees plenty of wrong in the maltreatment of innocent creatures, may be that if the flesh of an animal is both ethically and sustainably produced, then there is no, or little, actual harm done. There may admittedly be many others who share this notion. But we are not talking hypothetically here, and any compassionate resolution to producing meat (if there may be one) whilst continuing to use a system revolved around factory farming, still seems a long way off. Thus, whilst factory farming is still legal, the only morally right thing to do seems to be abstaining from consuming meat and all other animal products outright. The alternatives are too perilous, such as the ‘Eat What You Kill’ movement in the US, which involves hunting for wild game. Eating meat will always implicate involuntary murder to an intelligent animal, and this again raises animal rights issues which for the purpose of this discourse I shall not go any further into than already discussed, as we shall now turn our attentions to another animal issue which is prevalent within our society: using animals for fashion.

Using animals for clothes and materials.

Animal products still loom large in fashion. Groups such as PETA have done lots over the years to try to curb interest in fur, such as documentaries released in 1994, which showed ranchers abusing small animals such as minks and chinchillas by clipping electric wires to their genitals and injecting them with weed killers. There has been some success on their part in the reduction of fur use in the industry, with the pressure they’ve put on mainstream retailers such as Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss, Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger leading to these particular brands having stopped using fur altogether. There was even a campaign fronted by supermodels who were willing to pose nude, such as Naomi Campbell and Cindy Crawford under the guise "I'd Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur”, which achieved some success in changing people’s perceptions of fur. Leather is another issue however and is still undoubtedly the most widely used form of animal material. There has been documented evidence showing cows being skinned alive, having their horns clipped and tails broken, and dying before they even reach the slaughterhouse. All for the purpose of producing leather.

Does it follow then that if we shouldn’t eat animals due to the horrors of factory farming then we also shouldn’t use their dead carcasses to make boots, sofas and other fashion and non-fashion related accessories? If we agree that the fist premise (that we shouldn’t eat animals) is sound, then the logical answer to this question would appear to be yes. There is however, more to this case than the mere assumption that if it is wrong to do one action then it is morally wrong to do the other. There is a clear distinction between eating an animal as a source of nourishment and that of using their corpses for materials such as leather, fur and suede. One could even argue that eating animals accords much more with nature than the sheer use of their flesh or fur for luxury items. If we therefore argue in the other direction then; that it is fine to eat animals but not to wear them, could we then ask that if an animal were to die of natural courses, would it then be okay to use their body for luxury materials? After all, it would be going to waste if it were simply allowed to rot to mort. This argument could similarly be applied to whether or not we should eat an animal that is known to have died from natural causes and likewise is another easy argument to disengage.

If we are to use the body of any animal - be it that they died of natural causes or not - there is something inherent within this in which we are admitting. To use the body of another animal’s flesh (or fur) to form materials out of is to acknowledge their skin as a type of substance which can now be put to use, as the former “possessor” of it (the animal in question) no longer has their own needs for it in regards to the purpose it originally served: that of insulation of the major organs and protection from external bacteria. If we’re arguing on the premise that its acceptable to now use the skin of an animal because it is already dead and thus the material is ‘going to waste’, then we can likewise admit something else which seems rather sinister. Let us say for example, that if we were to use the flesh of a cow that had died from natural causes to make leather, would it then not also be equally morally acceptable to use the flesh or fur of other creatures who are dead and thus whose flesh is free to use? Could we begin to use dead pet dogs or cats as fur? Could a human who had no friends or family form an excellent material to be used as upholstery? As, similarly to the case of the cow that died from natural causes, the body of a human (particularly one with no relatives) would likewise also go to waste if simply left to rot.

If we believe in the argument that it is okay to wear fur or leather because the animal is already dead, then under these circumstances using the skin of a deceased human who had no family members should likewise be acceptable. Since however we do not find it morally acceptable to use human flesh for materials in our current society, we shouldn't so lightheartedly take our attitude to the wearing of other non-human animals as shoes, jackets and other items. It should matter little that the animal used in question has died from natural causes, or that the sheer reason the animal existed was because humans helped produce it. The intrinsic point here is that just because the flesh of an animal becomes available to use - be it human or non-human - this neither gives us the right nor makes it a viable reason to use it. If we value the flesh and fur of humans and pets, it makes little sense except for purely egotistical reasons why we shouldn’t therefore also value that of other non-human animals.

Admittedly, there is a different issue to the use of animal’s skin purely for fashion. That is, the use of a creatures skin in the form of medical operations performed on humans, such as skin graphs. We can apply a similar argument to one raised in the previous section in this instance. If we believe that it is acceptable to use, for example, a pig’s skin as a skin graph for a fellow human then let us then ask ourselves the question: Would it be likewise acceptable to use a less intelligent human’s (than a pig) skin instead of the pigs? If our intuitions tell us ‘no’ for this case, then we should likewise apply the same argument for the pig, as we can therefore conclude we are basing our arguments on a species bias for our own species rather than using a rational, objective approach.

Let us do another thought experiment. Say a highly intelligent species of alien were to land on earth. After initially appearing to be peaceful creatures and befriending humans in a somewhat paternalistic sense, they begin sampling the food and customs of our land and come to the decision that they now too have a taste for animal flesh and also like the idea of wearing dead animal carcasses as fashion accessories. They then reach the conclusion that as humans are primitive beings in comparison to their own highly advanced level of intelligence, they believe it is justifiable for them to eat humans and wear our dead bodies as garments. They even then develop a taste for women’s breast milk and reproductive eggs and thus set up farms to extract women’s eggs and force them into lactation. Do we as humans call these actions unjust? Are we then not hypocrites? Or conversely, does their use of our flesh – being of a higher intelligence than us – then also justify out means in also using the flesh of other less intelligent species, in what Social Darwinian’s would label ‘natural selection’ or ‘survival of the fittest’? I don’t believe it does. Even if said aliens did decide to visit Earth and did develop a taste for human flesh (and breast milk) and wearing our dead carcasses as fashion accessories, this still wouldn't justify them in doing so, as they’ve clearly survived this far without doing any of those things, in the same way as how humans can easily – and many would argue more efficiently – survive without eating or wearing animal flesh. Their higher level of intelligence shouldn’t be of any concern in this issue, it simply further demonstrates that higher or lower intelligence isn’t the only mark by which to mark the moral actions of a species by and is therefore not a mark by which we as humans should judge on which basis we decide to eat or wear the flesh of other animals.

Granted, it could be argued that this situation could be altered if it was as a means of survival for a species. But that is simply not the case in our current economic climate, where the continuation of using animals for food and clothes is causing more detriment to our survival as a species than it is benefit. The truth is that wearing animals as a means of fashion isn’t a necessity and is incredibly difficult to justify. Wearing animals does not further ‘individuality’ or ‘liberalism’ in any sense, as the sheer act of wearing them in fact denies the liberty of the animal who is being worn. If it is indeed the influence of celebrities and supermodels that influence our fashion choices - as so often appears to be the case - this begs the question: wouldn’t the spirit of that of a true fashionista be one that expressed their own individualism rather than that of uniformity? When fashion comes to the cost of a creature’s lives merely for the sake of narcissistic matters such as appearance - these questions must be faced.

Now we have established the contradictory nature of our species preferences when it comes to food and fashion, we will at this point have a short say on the issue of using animals as a form of entertainment.

Using Animals for “Fun”: A Form of Slavery?

I shall keep this section succinct as the principles we’ve already raised already cover this topic to some degree, and by far the use of animals as food and clothes causes more destruction and harm than the entertainment industry. Nevertheless, using animals merely as a means of entertainment is still a prevalent issue. Are animals simply to be used for our entertainment? People who find no qualms about eating meat or wearing animal products surely shouldn’t care whether or not an animal in a zoo has a good life or not, should they? It would be wrong to assert here that even those who eat meat don’t care about the wellbeing of animals, despite by doing so actively contributing to a system, which produces and enslaves animals at the cost of their wellbeing and to the degradation of our natural resources and environment.

Zoos may not in practice be as bad a place to live for an animal as say, factory farming, but there is still less than sufficient standards of living available to animals forcibly entertaining people, living in slave-like conditions in zoos as oppose to the wild. The point of slavery may seem an extreme and perhaps even ironic example to use, coming from a middle-class white man whose, for all my limited knowledge, may have distant family members who in some way contributed to or tolerated the abhorrent acts of slavery. I say this word with no agenda and no light taking of the circumstances regarding slavery. In fact, there are even relative Holocaust survivors who have compared the acts of factory farming to that of what their family members went through in concentration camps. There may even come a time when our future relatives look back at the acts we are committing now with the same level of contempt we do for acts such as these. The act of slavery, as defined in the dictionary is “The state of one bound in servitude as the property of a slaveholder or household. ” The interesting word to highlight here is ‘slaveholder’. When we use this word we are admitting that by forcing one to act against their will, and benefitting from their contribution without their permission or reimbursement for their acts, is thus to place an act of slavery upon that being. These are precisely the type of acts that are committed against intelligent, sentient and emotion-capable beings when we use their services against their will. So in a sense, one could argue that using animals as means of food, fashion or entertainment is akin to becoming a slaveholder by association. It is completely irrelevant if a slave happens to be the same species as us or not. By using animal products in this manner, as much as we may not like to admit it, we are actively participating in an institutionalised form of slaveholding. There may be some out there who think this example to be too extreme, and hope that we focus on problems within our own species before tackling the myriad issues regarding our treatment of animals. To that argument I simply reply that until we solve the issues regarding the treatment of non-human animals, then our lack of empathy will simply never allow us to solve the issues we have with each other as humans.

Conclusion

Not only would the abolition of factory farming and rearing livestock for food help prolong our environment as well as provide more food for the poor, developing more empathy for other species could in turn improve relationships between other humans and different nations. To use an example, 85% of the world’s soybeans are currently used to feed to livestock. So is notoriously one of the worst grains to grow for the environment and due to the demands of the agriculture industry we are having to produce excess amounts of it as feed for cattle, which could instead be used as food to give to the poorest regions of the world. In total, 51% of all of the world’s grains grown are fed to livestock. If that amount were fed to the most deprived parts of the world, it would be enough to end world hunger and famine, meaning not only do we impede the lives of animals every time we decide to eat animals, but also that of our fellow humans. If there are not enough reasons to abstain from eating animals simply from the perspective of animals also having rights, there clearly is from the argument of fellow human beings also having rights to better lives.

There are also health issues to consider. One fascinating example of the benefits of a plant-based diet lies is Okinawa in Japan, an area famous for having the highest amount of Centurions in the world. Could it be simply coincidence that they follow a mainly vegan diet with only the occasional meal including fish? They haven’t adapted this diet for ethical reasons, as it is largely due to both cultural and health issues. It is a point however in which we in the West could do well to adapt and in doing so, could increase longevity as well as lead a more healthy, sustainable and ethical life. Nutritionists agree that a plant based diet offers more than enough lean healthy protein, which is sufficient to supplement the human body. In fact, human breast milk contains less protein than any other species of mammal including that of rats, demonstrating our obsession with protein is both completely unwarranted and unnatural. This false belief that we require so much protein is perhaps one of the reasons as to why humans generally consume around twice the amount of daily protein they require, which is largely due to excess meat and animal product consumption. Other health issues arise such as consuming animal mucus (in all dairy products such as milk) as well as animal hormones (found in all meat and dairy products). In a society which is increasingly developing more and more dietary related diseases and illnesses, perhaps we would be wise to follow the example of the citizens of Okinawa.

Based on what we now know in regards to the capabilities of other species, as well as the cost to the environment of rearing them, even a staunch speciesist who, in light of all the evidence which suggests otherwise, still holds the false assumption that humans are far superior to any other race - within our limited knowledge - must then be forced to admit that if it is the survival of the species of Homo sapien which is so important, then it would be in hers (and that of the human race) interests to refrain from eating animal products. Thus even a speciesist argument must inevitably lead to some sort of reduction in our animal consumption habits - if not entirely. We now produce enough food on the planet to feed 10 billion people, a figure which is massively unsustainable. Refraining from eating animal products would help cut this figure down drastically, causing the demise of industries that make money from exploiting the environment and rearing animals to live in unthinkable forms of existence, meaning resources could be put to better use by aiding fellow humans rather than destroying the planet. For the further continuation of our own species, it is now imperative we address our dietary and fashion choices for the purpose of a happier planet, and possibly as a means of evolving any further. Eating animals is a part of our evolutionary past. As rational beings who are capable of empathising with other creatures such as cats and dogs, it need not play any part in our evolutionary future.

Photo gallery

Content available in other languages

Want to have your own Erasmus blog?

If you are experiencing living abroad, you're an avid traveller or want to promote the city where you live... create your own blog and share your adventures!

I want to create my Erasmus blog! →

Comments (0 comments)