Famine, Affluence & Morality in 2017

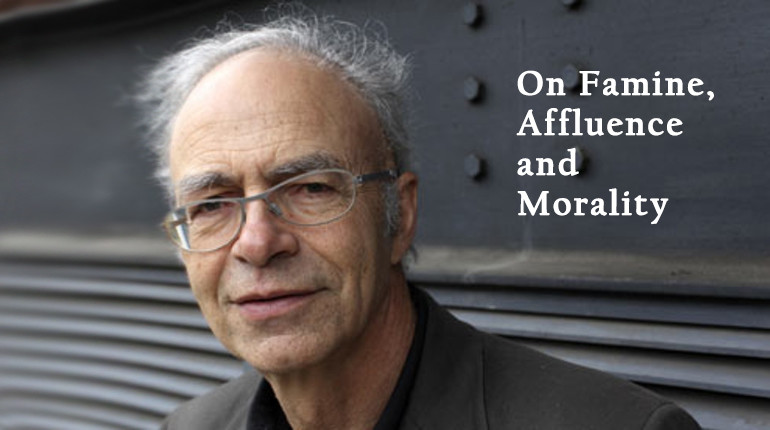

In his seminal 1971 essay entitled 'Famine Affluence & Morality, Peter Singer outlined issues at the time regarding the then refugee crisis in Bengal, India. The aim of the text however is rather general and is supposed to be applicable to any current world disaster or crisis and thus elements of it still ring true today. Thus, 46 years on, Singer's work still has huge influence on a global scale, with his TED Talk influencing many, as well as his work within the movement 'Effective Altruism'. Singer believes people in affluent Western countries have a moral obligation to donate far much more money than we currently do in international aid towards famine relief. He argues that because wealthy nations don’t contribute enough towards global famine and disaster relief, that we as individuals must take responsibility into our own hands. To do this, he believes we need to drastically alter our ‘moral codes’ in order to help those who need it most.

Singer argues that:

- “If it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

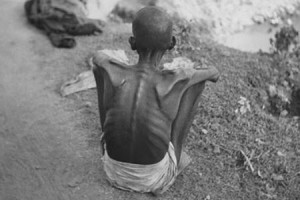

This is a difficult argument to disagree with. Singer believes that simply in virtue of living in a privileged society where our taxes don’t contribute enough to global aid, then this alone is justifiable enough a reason for us as individuals to help those less fortunate than us rather than rely on the state to do so. He follows up this argument by assuming that if we agree that suffering and dying from starvation is bad - which is likewise difficult to disagree with – then by donating more money, we are not really losing anything of moral significance (equivalent to starving to death).

Singer states our obligation to aid others does not decrease with distance and presents possible objections, such as the objection that one ought to help those nearby before helping those far away. However, this can no longer be argued. His own description of the world now posing a “Global Village”, where one can just as easily - if not more efficiently - help someone in a different part of the world as they can with helping someone who lives ‘on their own block’, means we are now all faced with ethical dilemmas.

Positive and negative duties

A Positive duty is seen an obligation to perform an act, on the part of the agent (or State) on whom it is imposed. A negative duty thus implies refrain on the part of person (or State) on whom it is imposed. Traditionally, negative duties have been considered more stringent than positive duties. However, occasionally even States admit a (lack of) distinction between the two. One example could be that of Britain paying international aid to past colonies such as India.

Whilst it is true that British citizens of today can’t be held accountable for the acts of colonialism, British tax payers still contribute international aid to India, even if it is not directly due to the past wrongs done to them. Conversely, Britain is not directly responsible for the famine crises in East Africa but also offers aid to these countries; an implicit admission by the British Government that these countries would also be left ‘worse off’ without such intervention, in the same way as India was following Colonialism.

Accordingly, Indian MP Dr Shashi Tharoor took to Oxford last year to say his piece about why Britain owes reparations directly for the wrongs of Colonialism. The video of his speech went viral, with subsequent polls of people in favour for Britain paying more aid to India, in the same way as Britain currently pays aid to developing countries for which they never previously Colonised. This puts the idea of positive and negative duties back into the equation. If Britain see the need in paying aid to these countries, surely they should try to rectify previous wrongs? Cleary there is now a need for both positive and negative duties, not just on a state level, but on an individual one too.

The idea of positive and negative duties within this context is similar to the idea of taking a life and letting someone die. In both circumstances, there is an option to do something; that that duty is either active - (the ‘murder’) e.g. Britain’s acts against India, or passive (the ‘letting die’) e.g. Britain if they chose not to aid East Africa - is of no moral significance, as both result in the ‘death’ of a country, which could be prevented. In the context of global aid, that one actively exploits persons from another country, leaving them worse off, or conversely fails to offer them any assistance - similarly leaving them worse off - is morally speaking, exactly the same. In both examples an option is available to offer assistance (as in this example) and thus, on some levels, failing to aid other countries is of no real moral difference to actively exploting them.

What next for Globalisation?

Globalisation itself does give us reasons to question the difference between positive and negative duties. We do affect other countries for the worse through contributing to actions such as global warming, but also because we exploit resources by using their citizens as means of cheap labour and similarly because we have the resources to end the starvation occurring in such countries.

Now that we can just as easily help someone overseas as we can help someone in our neighbourhood, do we not - considering those in other countries live in absolute rather than relative poverty – have even more obligation to help those living overseas? Similarly, how can we justify our own spending habits on products we don’t necessarily need when we could instead donate that money?

Instead of buying bottled water, we can drink tap water, whereas people in parts of the world have to walk for miles every day just to find clean drinking water. The money we would save from drinking tap water rather than buying bottled water could be donated to charity. We could also shop in supermarkets rather than eat out at restaurants and use that money to donate to charity. Contrast this with some people dying of starvation in other countries who don’t have access to any food whatsoever.

When we consider the technological advancements that the internet have provided us with, where one can send money, apply for visas for other countries and plan trips all from the comfort of our own home, we realise that Singer’s prophesising of the world as a “Global Village” came all too soon.

Because of these ‘Global Village’ effects of Globalisation we have moral obligations through which we must act, or we are indirectly responsible for allowing others to die. Because of these effects, and the wealth of knowledge available to us through resources like the internet, the startling reality of our duty to act puts into question the situation between positive and negative duties, as there is now no real barrier we can point to in regards to how we get aid over to other countries.

Photo gallery

Want to have your own Erasmus blog?

If you are experiencing living abroad, you're an avid traveller or want to promote the city where you live... create your own blog and share your adventures!

I want to create my Erasmus blog! →

Comments (0 comments)