A (Brief) History Of British Club Culture in Politics

There has been a long history of repression in regards to club culture in the UK, particularly in regards to the 90s ‘rave’ scene. The 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act was a wide-encompassing, contrasting legislation that covered various aspects of law, but most of it was clearly targeted at preventing the activities of particular modes of alternative culture. The key targets of this radical legislation were squatting, concise action against the occupation of land and outdoor parties. Specifically, it attempted to end unlicensed dance parties, something that had become a necessity of weekend life for a lot of people in both urban and rural areas of the country. These parties were often free of charge; music and other essentials were provided by committed teams of sound engineers, van drivers, DJs (who would often play hard techno and breakbeat style tracks, differing from the gospel-styled ‘garage’ played across the country at the time) phone operators, event promoters and so on, who would pick a location, organise the party, and spread details of the time and place through various fields of promotion. The parts of the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public Order regarding raves formed one of the most direct interventions of a British government in the twentieth century, some of the laws included sanctions for the first time against music and, what the Criminal Justice & Public Order Act declared: ‘sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats’.

The Act was passed by Parliament without any real challenge from any of the major political parties. This is arguably what needs the most clarification. It is obvious why John Major’s Conservative government passed this legislation; his party were falling behind the Labour party in opinion polls, had succumbed detrimental effects to both its economic and political integrity, and he himself was being pressured by his own supporters to further reinvigorate the concepts put forth by his predecessor and former Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. Pivotal to Thatcher’s ideology was a clear antagonism toward marginalised groups - in regards to ethnicity, sexuality or otherwise – who happened to question the ideas of ‘British’ culture, accompanied by an authoritarianism that has become associated with Thatcherite conservatism; thus partly clarifying its support.

There are other logical reasons why the Government was so eager to suppress rave culture, particularly its non-commercial aspects. The UK’s brewing industry has long been a contributor to the Conservative Party, and was understandably concerned with the alleged dip in alcohol consumption in relation to the surge in availability and use of dance drugs. Free parties scarcely made any profit, and therefore were seen as a threat to many mainstream leisure organisations. But this is not enough to explain why the legislation against these parties took the shape in which it did, and why it garnered such little opposition from other political parties. It could be suggested the only reason for this apparent absence of opposition is that this act is merely part of a long cycle of suppression of social and sensual pleasure.

This opposition to intoxicated crowds appears alongside the creation of the modern subject; it is pivotal to how the discourses of possessive individualism were expressed at the early stages of capitalism throughout Northern Europe. The impression that human beings are rational subjects, singular and irreducible, is resisted by the euphoria and unity of dance. As Paul Spencer points out regarding dancers from all over the world ‘In their ecstasy they literally stand outside’.Standing outside of oneself, particularly when displaying individuality, is what the related areas of the subject, which has been prominent in European culture since at least the seventeenth century, are notably hostile toward, as the memoirs of Sigmund Freud indicate:

- ‘Separating oneself from internal or external objects is traumatic because the uneasy feeling of transition reveals, once again, the primal anxiety of difference, of the “conscious of living”. Thus the liminal meaning of the trauma of the birth: “To this real making of his own ego, the individual reacts in the actual separation experience with fear which is not an original biological reaction in the sense of the death fear, but on the contrary, is life fear, that is, fear of realising [one’s] own ego as an independent individuality.”’

There was another important reason behind why there was such significant backing from political parties towards the 1994 Criminal Justice Act: rave culture was linked to recreational ‘drug’ use and was viewed by some as a genuine target for the enforcement of strict legislations. How a preconception like this can appraise British public legislation in the modern era is testament to the prolonged impact of Puritanism on British politics, as I will elaborate.

The War On Drugs: A Failure From the Start?

In 1998, the new Labour government made former Police Chief Constable Keith Hallewell their new ‘Drugs Czar’ (a term that was originally used by George Bush’s organisation), meanwhile theIndependent on Sundaynewspaper featured a widely publicised campaign regarding the decriminalisation of cannabis. (The Independent, 1999) The BBC televised a debate on the matter in May 1998, after the publishing of a Government White Paper signaling no major change in approach for a blueprint agenda still led by the opinion that ‘drugs’ – a comparable, undifferentiated type of experience. The White Paper featured actions that could mean anyone possessing cannabis would have to undergo treatment for their social disorder. The gap between youth culture and the British Government was highlighted in December 1997, when the son of home secretary Jack Straw received a caution from police for supplying a newspaper journalist with cannabis.

More recently, in 2009 former Drugs Chief Advisor David Nutt was dismissed for - amongst having other drug-centric opinions - claiming that alcohol was more dangerous than ecstasy. This again demonstrates the willingness of the government to oppose rave culture, emphasising the Government’s affilliations with the UK Brewing Industry as mentioned earlier.

Legal Highs

Since this we’ve seen the Government’s fight against illegal substances weakened by the popularity surge of legal highs such as mephedrone or ‘MCAT”. The loopholes that allowed these sales to go unpunished have brought drug laws into disrepute, questioning their real significance in modern society; further demonstrated by Ireland’s recent episode where possession of ecstasy was completely tolerated for 48 hours due to a legal technicality.

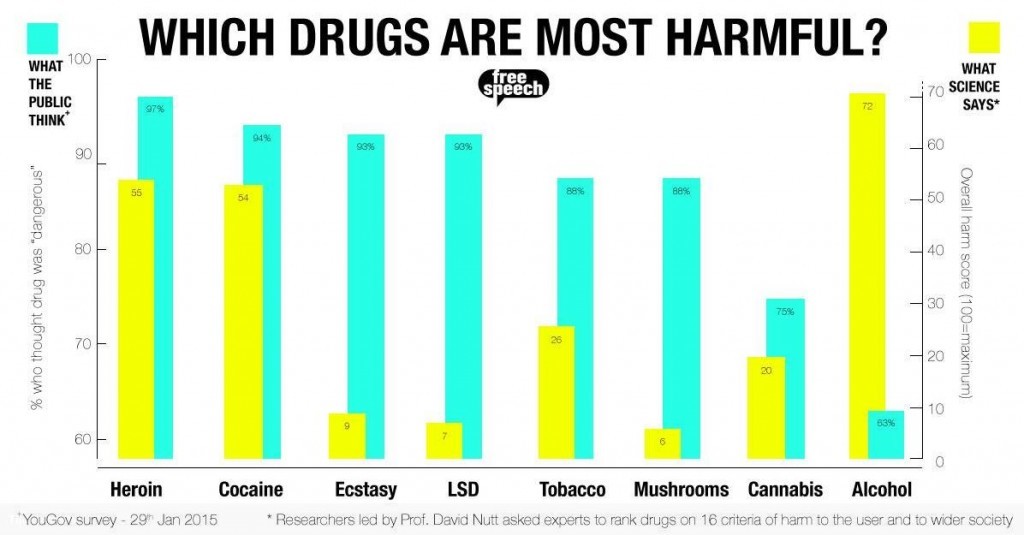

Figure 3, YouGov, 2015

Interestingly, a recent survey conducted by former Drugs Advisor to the Labour government David Nutt shows the general public’s obliviousness to the harms of alcohol and tobacco compared to other drugs whilst perceiving other substances as far more harmful than they actually are. It could be suggested that prohibition is causing more harm than good, degrading the quality of drugs to forms such as “street ecstasy”, whereas according to YouGov, as demonstrated above, pure ecstasy or ‘MDMA’ as it is chemically known, is less harmful than alcohol, tobacco and surprisingly even cannabis.

It is of course irresponsible to suggest ecstasy is entirely safe. There were 123 deaths reported in England and Wales alone spanning from 2008-2012. Compare this to up until 1995 when ecstasy had accounted for 60 deaths in the whole of the UK, and it becomes clear that prohibition does not appear to be helping the situation. However, although these deaths have been attributed to ‘ecstasy’ as a cause, there is no way for us to be certain what chemical or substance actually caused these deaths as without proper purity sanctions, consuming unlegislated substances becomes a risky game. Another reason for this inaccurate public preconception could be down to roles the media, as well as the British state play. Following the death of 18 year old Leah Betts in 1995 (the first death believed to have been caused by ecstasy in the UK), the Government used posters and billboards of Leah next to the slogan ‘Sorted: Just one ecstasy tablet took Leah Betts’. (BBC, 2005) This formed what we can only perceive now as a blatant act of propaganda used by the government in the war on drugs to influence the general public. One could compare these acts of fear mongering to those of anti-nazi propaganda similarly used by the British government during a different type of war - WWII.

Leah’s death was attributed to ‘hypernatremia’ (water intoxication), which is recognised as one of the three main fatal causes of deaths associated with ecstasy along with hyperthermia and cardiac failure, differing from other drug death related causes of death such as overdosing: it would take about 1.5–1.8g of MDMA per kg of bodyweight to overdose on ecstasy, a sizeable amount even for the more experienced user. (Knott, 2015) Postmortems confirmed that her death was not directly caused by MDMA (Ecstasy), but instead the large amount of water she consumed. (BBC, 1995) Following the inquest into her death, toxicologist Professor John Henry, who had at this point already warned the public about the dangers of death caused by dehydration as a result of taking ecstasy stated: "If Leah had taken the drug alone she might well have survived. If she had drunk the amount of water alone she would have survived." (BBC, 2005)

Again in November 2009 the mass media played a huge part in the sensationalisation of a new ‘legal high’ mepehdrone, also know as MCAT or ‘meow meow’. Mephedrone was marketed as ‘plant food’ and thus could legally be sold online and across stores in the UK with the slogan ‘not for human consumption’ on the packaging. This emphasises not only the changes in society towards the type of drugs people consume, from MDMA to MCAT, but how they go about purchasing them, via a form of virtual drug-dealership. On 24th November 2009, schoolgirl Gabirelle Price died as a result of taking mephedrone at a house party in Brighton. Two days later, The Sun featured a story regarding an unnamed teenager from Durham with the headline ‘User rips off scrotum on legal drugs’, which (unsurprisingly) was later picked up by the British press.

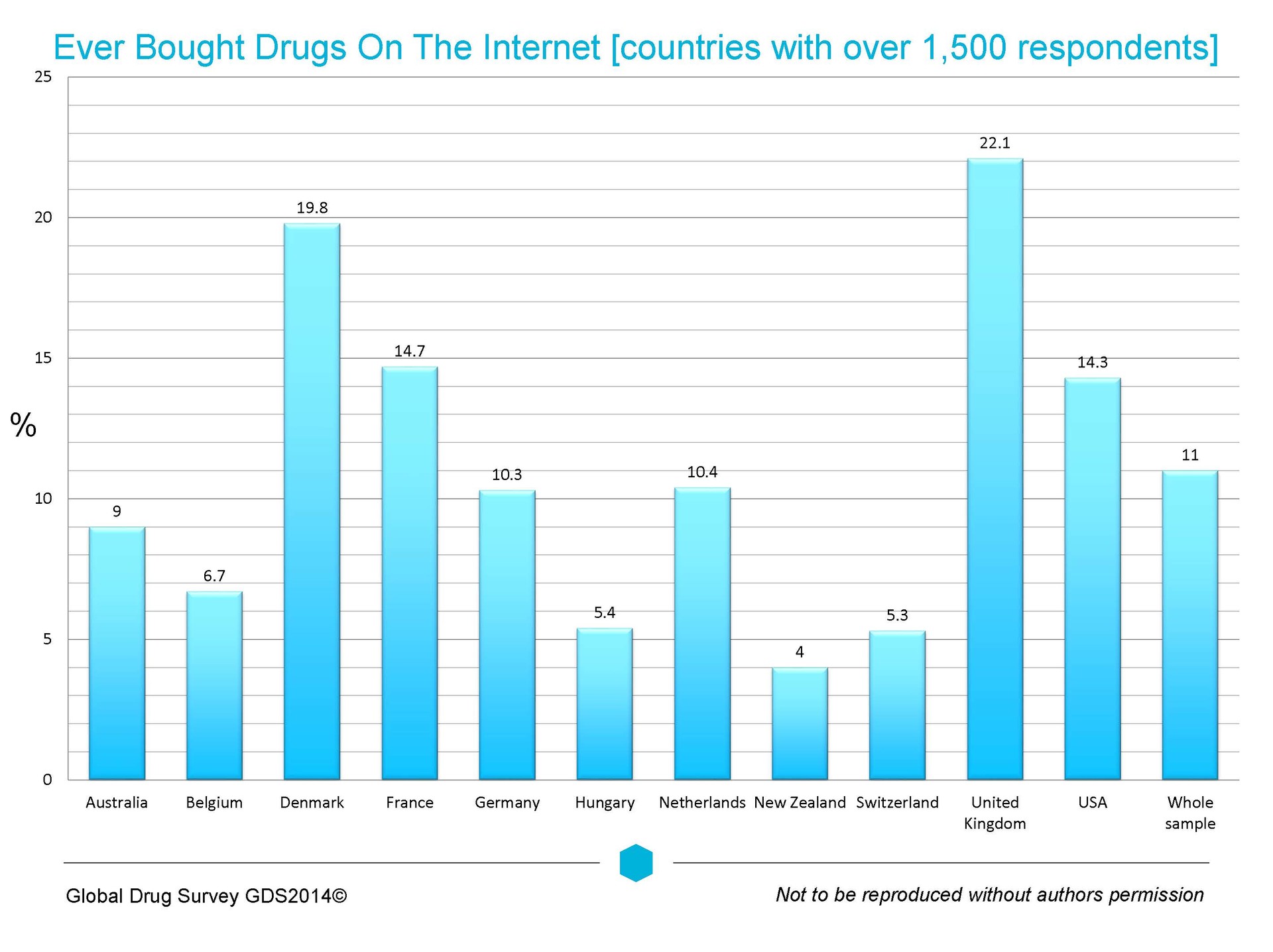

In a recent survey shown below, participants from various countries were asked if they’d ever purchased drugs online. The U.K. topped the list, signifying the failure of Britain’s war on drugs’ whilst proving the dangers prohibition causes: when people cannot buy something legally, black markets are certain to appear. This was demonstrated further by websites such as Silk Road or 'The Dark Web' which used the cryptocurrency Bitcoinin transactions to deal with customers anonymously in order to avoid detection from the authorities. The website ran successfully for three years before the organisers were eventually tracked down by police and convicted for drugs trafficking and other offences.

Figure 4, GlobaDrugsSurvey.com, 2014

Legal and Other Issues

There are many issues regarding the debate over drugs. Firstly, drug prohibition leads to the imprisonment of thousands of citizens due to drug-related offences each year: more than 12 percent of Britain’s prison population have been imprisoned for drug related offences, with imprisonment for such offences growing rapidly between 1993 - 2012. Imprisonment could be viewed as a form of brutality, and the application of this brutality should naturally demand justification. Secondly, prohibition simply leads to people seeking loopholes to legally buy or sell drugs, as is the case with legal highs and the recent 48-hour-only legal ecstasy law that came into effect in Ireland. Lastly, to incarcerate so many people for drug offences must come at a huge cost to the state, as must the loss of potential for tax revenue that could be gained for the legalisation of substances that are equally, or in some instances, less harmful than alcohol and tobacco.

These resources could potentially go towards plans with values deemed much less contentious than drug prohibition. Lastly, many professionals who work to stop the harm that drug use can obviously cause, concur that the main source of this harm is due to the fact these drugs are made illegal. As there is no genuine regulation, participation involvement in the drugs market is inconsistent; there is no purity control and in some instances, over-purity can be hazardous for the user. (Spiegel, 2013) Violence and crime are present in any black market. Therefore if the drugs market was controlled and regulated, it could potentially be a safer, more peaceful environment; illegality causes higher drug prices, pushing users and addicts down criminal paths as a means to pay for them. Furthermore, as I have mentioned, drug legality is a discourse which origins lay in nothing more significant than sexist and racist preconceptions that today most people would deem abhorrent.

If we view drugs as simply a modern ‘creation’ amongst many other creations that distinguish modern life, it could be argued other forms such as cars for example, are arguably more dangerous: nearly 1.3 million people die in road crashes each year, with on average 3,287 deaths a day worldwide. With this in mind, why then are the government and cultural establishments so opposed to recreational drug use? This question can be answered by viewing the subject of drug prohibition as expressed at the meeting point of multiple various histories. A notable starting point in British drug prohibition, as Andrew Sherratt notes:

- It was the increasing social tensions and consequent imposition of discipline (aimed initially at munitions workers) at the time of the First World War and its aftermath, that produced first the UK licensing laws and then the Dangerous Drugs Act (1924) that put an end to the socially acceptable use of these drugs. ... These circumstances led to their stereotyping and an ethnocentric reaction against ‘alien drugs’ and their predominantly working-class users; in Britain the association of opium with Chinese immigrants was an important factor in the development of attitudes to it in the nineteenth century, while the association of cannabis with West Indians repeated the process in the early 1960s and led to the inclusion of cannabis and its products in the Dangerous Drugs Act. (1924).(Goodman, p.221995)

Sherratt accurately creates a parallel between the enforcement of drug and licensing legislation. This came at a time when the US Government also enforced prohibition on the sale of alcohol, a law which span the entire 1920s. Whilst particular groups (such as British munitions workers) might have at times became areas of concern, there was generally a change in attitude from Western society towards pro-regulation and prohibition of the consumption of intoxicating substances. It was not only Government agents who shared this idea; the first Labour member of British parliament Keir Hardie, stood for election with a firm prohibition policy.

To understand why this change in attitude happened when it did, we must considerwhatrather than why; what shape did historic changes in attitude take? Marek Kohn depicts this era in detail in the book 'Dope Girls' by addressing how drug prohibition was implemented through both legal and cultural terms in Britain as a form of reaction to many of the social crises – such as the war – that were happening at the time. Kohn underpins the initial fear towards ‘drug’ use by mapping its history: ‘

- ‘London never did lead the world in drug culture. As a case study, the interest of the British drug scene lies in the attractive neatness of its sudden mushrooming on virgin soil. It has a deeper fascination, as a symptom of a crisis in Britain’s evolution as a modern society. Drug panics derive their electric intensity from a concentration of meanings: in Britain the detection of a drug underground provided a way of speaking simultaneously about women, race, sex, and the nation’s place in the world’ .It was a symbolic issue in which a larger national crisis was reworked in microcosm’. (Kohn,p.4 1992)

The Great War was a critical point in Britain’s imperialism. During this time, many ethnic minorities immigrated to Europe due to the negative impact imperialism played on the economic climate. This was further reinforced by the continuation of imperial management formations throughout Western society. Political discourse began to arise due to growing concern regarding imperial white identity; philosophies built around ideas of racial hegemony and the wish to shield Europeans from ‘deterioration’. Initial pro-drug prohibition debates centred around ‘drugs’ in particular as possible causation for this racial disaster. In some aspects, one could argue prohibition’s origins are the same of that of fascism, both built around ‘stereotypes’ and ‘disapproval’ British identity was threatened, with drugs seen as a possible cause to this threat, causing a call to prohibit them. As suggested by Kohn above, the initial drug prohibition legislated in Britain was implemented mainly as a reaction to fears that easily accessible drugs would encourage Caucasian women to associate, and possibly have sexual relations with other ethnic minorities.

Likewise, according to Kohn, there was also a common perception by senior figures during this period that ethnic minorities were subordinate, and seen as less intelligent (as were females to men). Drugs were not prohibited due to public health issues or concern for people’s wellbeing, but due to the fact they were linked to ethnic cultures and women who for over a century experienced emancipation from male oppression, both socially and sexually. Prohibition discourse during this period was centred around the idea of women and ethnic groups being inferior.

Although it may no longer seem admissible to publically argue that ethnic groups and women are subordinate, the ways in which this inferiority was characterised nearly a century ago are still pivotal to certain discourses today. Ethnic groups and women were seen as less sensible and generally less able than Caucasian men, and therefore were less likely to gain the same bourgeois place in society that white men could. Anti- drugs discourse has arguably for a long time been – and continues to be – viewed as suspect through that discourse; to take part in schemes that diminish the ability to reason, and to engage in such simply for acts of pleasure, in this context appear discreditable. Drug encounters are viewed as provocative to many of the fundamental terms according to which, thus the metaphysics of the subject must be considered and comprised. Distinguishing the body from the mind and soul could become problematic in the event of having one’s mind altered through the consumption of drugs and alcohol. It is worth noting that British law still does not permit advertisements which sell alcohol for the purpose of getting the consumer drunk, therefore it is often advertised based on quality and/or taste.

Considerations

Anti-drugs discourse finds itself still connected to the hegemony of Puritanism. This is emphasised by modern day opinions that oppose drug decriminalisation. The arguments against drugs claim drugs remove the consumer’s aspirations in life, making them lazy; this is where the ludicrous theory of ‘anti-motivational syndrome’ stems from. Anti- motivational syndrome is a medical term for severe lethargy, a term that finds itself still quoted in government documents as one of the potential side-effects of cannabis use. The continuance of laws that imprison people for the possession of substances used for the purpose of pleasure whilst simultaneously causing lethargy, emphasises how much Puritan discourse still to this day influences both judicial and political, and even medical discourse.

It seems that dance music, being the hedonistic culture it is, has rather typically been resilient towards the politico-cultural dominance of Puritanism. Rave culture and its successors have arguably been socialist developments, creating a form of politics that sought to form a utopia where the people were as one, unified by their dedication of committing their life to hedonistic activity.

Photo gallery

Want to have your own Erasmus blog?

If you are experiencing living abroad, you're an avid traveller or want to promote the city where you live... create your own blog and share your adventures!

I want to create my Erasmus blog! →

Comments (0 comments)